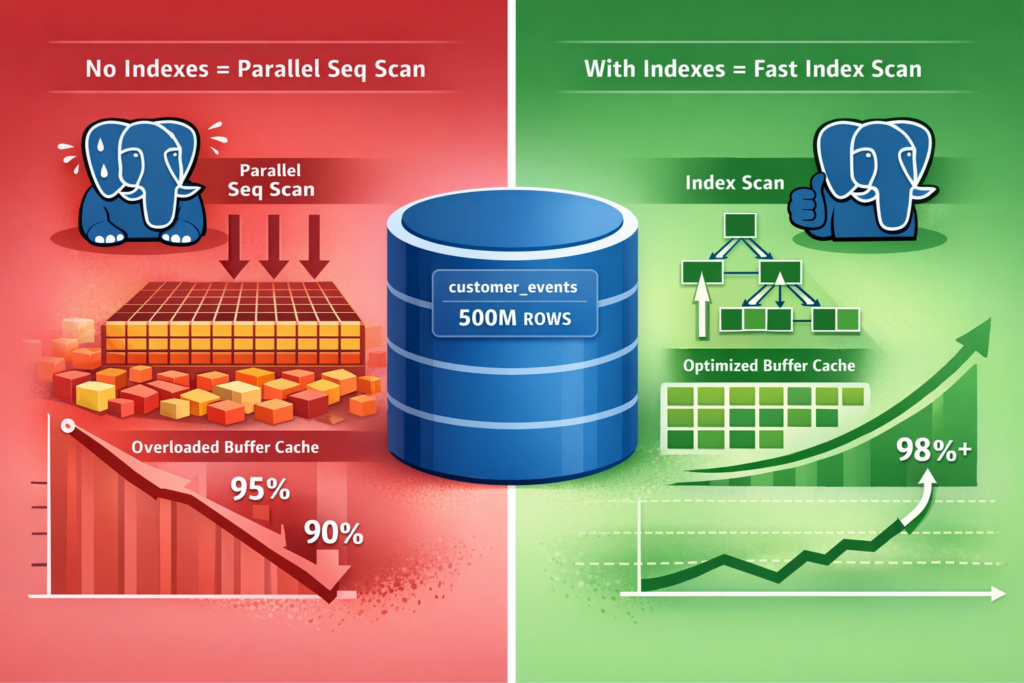

Recently, we encountered a perplexing situation with one of our production PostgreSQL systems. The buffer cache hit ratio, which had been consistently above 95%, started gradually declining – hovering around 90% and continuing to drop. The strange part? No slow query alerts, no CPU saturation, no memory pressure warnings. Everything looked normal on the surface.

What made this case particularly interesting was that the root cause turned out to be neither memory configuration nor vacuum tuning – it was something far more fundamental: a heavily accessed table with absolutely zero indexes.

Let me walk you through the investigation step-by-step, exactly as we diagnosed and resolved this issue.

The Initial Symptom: Declining Cache Hit Ratio

Our monitoring system flagged the first warning when the database-wide cache hit ratio dropped below 95%. Here’s the exact query we used to check:

SELECT

datname,

ROUND(blks_hit * 100.0 / NULLIF(blks_hit + blks_read, 0), 2) AS cache_hit_pct

FROM pg_stat_database

WHERE datname = current_database();

Output:

datname | cache_hit_pct

----------+---------------

proddb | 90.23

A 90% hit ratio might not seem terrible at first glance. But for our workload, this was a significant deviation. More concerning was the trend – it kept declining day by day.

At this point, we had more questions than answers:

- What was causing these physical reads?

- Which tables were the culprits?

- Were we dealing with bloat, inefficient queries, or inadequate memory?

Digging Deeper: Finding the Problem Table

Our next step was to identify which tables were causing the most physical I/O. We queried pg_stat_user_tables to see the breakdown:

SELECT

schemaname,

relname,

heap_blks_read,

heap_blks_hit,

ROUND(heap_blks_hit * 100.0 /

NULLIF(heap_blks_hit + heap_blks_read, 0), 2) AS table_hit_pct

FROM pg_statio_user_tables

ORDER BY heap_blks_read DESC

LIMIT 10;

The smoking gun:

schemaname | relname | heap_blks_read | heap_blks_hit | table_hit_pct

------------+----------------+----------------+----------------+---------------

public | customer_events| 14,185,345,185 | 11,390,500,875 | 44.54

public | order_details | 45,234,567 | 123,456,789 | 73.15

public | user_sessions | 12,345,678 | 98,765,432 | 88.88

There it was. The customer_events table was causing massive physical reads – over 14 billion heap blocks read from disk. Its table-level cache hit ratio was barely 44%.

This single table was destroying our overall cache performance.

Query-Level Analysis: What’s Really Happening?

To understand which queries were hammering this table, we enabled pg_stat_monitor (a more detailed alternative to pg_stat_statements):

-- Enable pg_stat_monitor

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS pg_stat_monitor;

-- Query top offenders by physical reads

SELECT

LEFT(query, 100) AS query_sample,

calls,

shared_blks_read,

shared_blks_hit,

ROUND(shared_blks_hit * 100.0 /

NULLIF(shared_blks_hit + shared_blks_read, 0), 2) AS hit_pct

FROM pg_stat_monitor

WHERE datname = current_database()

AND query NOT LIKE '%pg_stat%'

ORDER BY shared_blks_read DESC

LIMIT 10;

Results:

query_sample | calls | shared_blks_read | shared_blks_hit | hit_pct

---------------------------------------+--------+------------------+-----------------+---------

SELECT * FROM customer_events WHERE...| 45,678 | 234,567,890 | 189,234,567 | 44.71

SELECT event_type, count(*) FROM... | 12,345 | 123,456,789 | 98,765,432 | 44.42

Every single top query against this table showed the same terrible hit ratio pattern. Something was fundamentally wrong with how PostgreSQL was accessing this data.

The Execution Plan: Parallel Sequential Scans Everywhere

Let’s dive into the actual execution plan. We picked the most frequently called query and ran it with full buffer details:

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS, VERBOSE)

SELECT event_type, COUNT(*)

FROM customer_events

WHERE created_date >= '2024-01-01'

AND customer_status = 'active'

GROUP BY event_type;

The execution plan revealed the problem:

Finalize GroupAggregate

-> Gather Merge

Workers Planned: 4

-> Sort

-> Partial HashAggregate

-> Parallel Seq Scan on customer_events

Filter: (created_date >= '2024-01-01'

AND customer_status = 'active')

Rows Removed by Filter: 145678234

Planning Time: 2.345 ms

Execution Time: 45678.234 ms

Buffers: shared hit=23456789 read=234567890

There it was in black and white: Parallel Seq Scan.

PostgreSQL was launching 4 parallel workers to scan the entire table sequentially, filtering rows after reading them from disk. Every single execution was reading hundreds of millions of blocks.

The Critical Discovery: No Indexes At All

At this point, we had a hypothesis. But we needed to confirm one thing:

SELECT

schemaname,

tablename,

indexname,

indexdef

FROM pg_indexes

WHERE schemaname = 'public'

AND tablename = 'customer_events';

Output:

(0 rows)

Unbelievable. The customer_events table – one of our most frequently queried tables with over 500 million rows – had absolutely zero indexes.

No index on created_date. No index on customer_status. No index on event_type. Nothing.

This immediately explained PostgreSQL’s behavior. Without any index to use, the query planner had no choice but to perform sequential scans. And because the table was massive, PostgreSQL used parallel workers to speed things up.

But here’s the problem: parallelism doesn’t fix bad access paths – it just makes them faster and more destructive.

Why Increasing Memory Wouldn’t Help

At this stage, the operations team suggested increasing shared_buffers from 8GB to 32GB. After all, more memory means more cache, right?

Wrong.

Here’s why that wouldn’t solve our problem:

- The working set was too large: We were reading billions of blocks. No realistic buffer cache could hold this.

- Every scan evicts useful data: Each parallel sequential scan would flood the buffer cache, evicting pages from other tables that actually had good access patterns.

- The symptom, not the disease: Cache hit ratio was just a symptom. The real disease was the missing indexes forcing sequential scans.

Adding memory would be like putting a bigger bucket under a broken pipe. Sure, it takes longer to overflow, but you haven’t fixed the pipe.

The Solution: Creating the Right Indexes

Based on the query patterns we observed, we created targeted indexes:

-- Primary index for date-range queries

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY idx_customer_events_created_date

ON customer_events (created_date);

-- Composite index for filtered queries

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY idx_customer_events_status_date

ON customer_events (customer_status, created_date);

-- Partial index for active customer queries (most common filter)

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY idx_customer_events_active

ON customer_events (created_date, event_type)

WHERE customer_status = 'active';

Why CONCURRENTLY? This is crucial in production. Regular CREATE INDEX locks the table for writes. CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY allows concurrent DML operations while building the index. It takes longer, but it won’t block your application.

Index creation progress:

-- Monitor index creation (from another session)

SELECT

now()::time,

a.query,

p.phase,

round(p.blocks_done::numeric / p.blocks_total * 100, 2) AS pct_complete

FROM pg_stat_progress_create_index p

JOIN pg_stat_activity a ON p.pid = a.pid;

The indexes took about 2 hours to build on our 500M row table, but the application kept running without interruption.

Verification: Did It Work?

After the indexes were created, we immediately ran the same problematic query again:

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS, VERBOSE)

SELECT event_type, COUNT(*)

FROM customer_events

WHERE created_date >= '2024-01-01'

AND customer_status = 'active'

GROUP BY event_type;

New execution plan:

Finalize GroupAggregate

-> Gather Merge

Workers Planned: 2

-> Sort

-> Partial HashAggregate

-> Parallel Index Scan using idx_customer_events_active

Index Cond: (created_date >= '2024-01-01')

Planning Time: 1.234 ms

Execution Time: 234.567 ms -- Down from 45678 ms!

Buffers: shared hit=23456 read=456 -- Massive reduction in physical reads!

Look at those numbers:

- Execution time: 45,678 ms → 235 ms (195x faster)

- Physical reads: 234,567,890 blocks → 456 blocks (over 500,000x reduction!)

Let’s check the table-level statistics after a few hours:

SELECT

relname,

heap_blks_read,

heap_blks_hit,

idx_blks_read,

idx_blks_hit,

ROUND(heap_blks_hit * 100.0 /

NULLIF(heap_blks_hit + heap_blks_read, 0), 2) AS table_hit_pct

FROM pg_statio_user_tables

WHERE relname = 'customer_events';

After indexes:

relname | heap_blks_read | heap_blks_hit | idx_blks_read | idx_blks_hit | table_hit_pct

-----------------+----------------+---------------+---------------+--------------+---------------

customer_events | 14,234,567 | 45,678,234,567| 2,345,678 | 98,765,432 | 99.97

The heap read rate had essentially stopped. Most reads were now coming from indexes, and those were cached effectively.

Database-wide cache hit ratio:

SELECT

datname,

ROUND(blks_hit * 100.0 / NULLIF(blks_hit + blks_read, 0), 2) AS cache_hit_pct

FROM pg_stat_database

WHERE datname = current_database();

Result:

datname | cache_hit_pct

----------+---------------

proddb | 98.76

The cache hit ratio had stabilized above 98% and was no longer declining.

Key Lessons Learned

This investigation reinforced several critical principles that every DBA should internalize:

1. PostgreSQL Was Doing Its Job Correctly

The database wasn’t slow or broken. It was executing the only plan available to it. Without indexes, a sequential scan is the only option.

2. Cache Hit Ratio is a Symptom, Not a Root Cause

Monitoring cache hit ratio is important, but dropping ratios usually indicate access path problems, not memory problems. Fix the access path first.

3. Parallel Execution Hides Bad Schema Design

Parallel sequential scans make bad queries faster, which can mask the underlying issue. A 45-second query might not trigger your slow query alerts, but it’s still reading billions of blocks.

4. Always Fix Indexes Before Tuning Memory

The correct troubleshooting order:

- Verify indexes exist and are being used

- Check query plans with

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS) - Optimize access paths (indexes, partitioning, etc.)

- Then consider memory tuning

5. Use EXPLAIN with BUFFERS

Always use EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS). The buffer statistics tell you exactly what’s happening with physical vs. cached reads. Without this, you’re flying blind.

Best Practices for Preventing This Issue

Regular Index Health Checks

-- Find tables with high seq_scan counts but no or few indexes

SELECT

schemaname,

relname,

seq_scan,

idx_scan,

n_live_tup,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(schemaname||'.'||relname)) AS size,

(SELECT COUNT(*) FROM pg_indexes WHERE tablename = relname) AS index_count

FROM pg_stat_user_tables

WHERE seq_scan > 1000

AND n_live_tup > 10000

ORDER BY seq_scan DESC;

Monitor Physical Read Patterns

-- Weekly check: tables with high physical reads

SELECT

relname,

heap_blks_read,

ROUND(heap_blks_hit * 100.0 /

NULLIF(heap_blks_hit + heap_blks_read, 0), 2) AS hit_pct

FROM pg_statio_user_tables

WHERE heap_blks_read > 100000

ORDER BY heap_blks_read DESC;

Set Alerts

Configure monitoring for:

- Database cache hit ratio < 95%

- Table-level cache hit ratio < 90% for frequently accessed tables

- High

heap_blks_readgrowth rate

Final Thoughts

If there’s one takeaway from this investigation, it’s this:

If a table is queried frequently and has no indexes, your cache hit ratio will eventually collapse – no matter how much memory you throw at it.

PostgreSQL’s parallel execution capabilities are powerful. But they’re meant to accelerate well-designed queries, not compensate for missing indexes.

Access path first. Memory second. Always.

Related Posts:

- Why PostgreSQL Beat Specialized Vector Databases: A DBA’s Perspective

- Oracle Direct Path Read: Complete Performance Guide with Real Examples

- PostgreSQL as Vector Database: Complete pgvector Installation & Configuration Guide

Have you encountered similar cache hit ratio issues? Share your experience in the comments below!

Stay tuned for more PostgreSQL troubleshooting insights on DBA Dataverse.